Photo of the week - August 25, 2015

East Point, Prince Edward Island, Canada. iPhone 6+.

Tuesday, August 25, 2015 |

Tuesday, August 25, 2015 |  Post a Comment in

Post a Comment in  photo of the week | tagged

photo of the week | tagged  canada,

canada,  iphone,

iphone,  prince edward island

prince edward island

East Point, Prince Edward Island, Canada. iPhone 6+.

Tuesday, August 25, 2015 |

Tuesday, August 25, 2015 |  Post a Comment in

Post a Comment in  photo of the week | tagged

photo of the week | tagged  canada,

canada,  iphone,

iphone,  prince edward island

prince edward island This is Part 5 of my series chronicling design, construction, and eventual delivery of a tenor guitar built by David Cavins. See Parts 1, 2, 3, and 4 of this series.

David recently posted an update of the build on his website. Things are moving quickly, and soon it will be time for the finish to be applied! (see Part 6 for the sunburst finish)

Last Sunday (8/15/15) some friends and I played a short set at the Lanchester Fiddlers Picnic in Atglen, PA. We called this impromtu band "John EZ and the Gigolos." I'm playing my Collings D1ASB, and the sound guy did a great job amplifying my guitar.

Thanks to Lynn for taking this videos, and to Jeff for editing/posting them.

Tuesday, June 2, 2015 |

Tuesday, June 2, 2015 |  Post a Comment in

Post a Comment in  photo of the week | tagged

photo of the week | tagged  alejandro escovedo,

alejandro escovedo,  ardmore music hall,

ardmore music hall,  fuji x100

fuji x100

I've had my Apple Watch for about a week now (42mm space grey Sport model with black band). This isn't meant to be a comprehensive review. Instead, here are some disorganized thoughts from the first few days of wearing/using it.

This is Part 4 of my series chronicling design, construction, and eventual delivery of a tenor guitar built by David Cavins. See Parts 1, 2, and 3 of this series.

A couple of weeks ago, David sent me some samples of sugar maple, finished with subtly different shading, to get my feedback. All of these are beautiful, but I decided to go with the second from the left. This is going to be a stunning guitar!

In addition, we've been talking about neck size and profile, as well as the location of the adjustment bolt for the neck. David is using a system that allows the neck angle to easily be adjusted without removing the neck (and potentially that allows the angle to be adjusted while the strings are tuned to pitch). This bolt could be accessed via the neck block, through the interior of the guitar. But I've decided I want to show off this awesome design feature, and he is building this guitar with the access point at the heel of the neck, where the whole world (or at least people playing the guitar) can see it. With feature this cool, you have to show it off. See more about the neck joint on David's site.

Rincón, Puerto Rico. Fuji X-E1 with 10-24mm lens at 10mm, f/10.

Tuesday, February 10, 2015 |

Tuesday, February 10, 2015 |  Post a Comment in

Post a Comment in  photo of the week | tagged

photo of the week | tagged  10-24mm,

10-24mm,  fuji x-e1,

fuji x-e1,  puerto rico,

puerto rico,  rincón

rincón

La Mina Falls, El Yunque, Puerto Rico. Fuji X-E1 with 10-24mm lens at 10mm, f/10.

Tuesday, February 3, 2015 |

Tuesday, February 3, 2015 |  Post a Comment in

Post a Comment in  photo of the week | tagged

photo of the week | tagged  10-24mm,

10-24mm,  el yunque,

el yunque,  fuji x-e1,

fuji x-e1,  puerto rico

puerto rico

Old San Juan, Puerto Rico. Fuji X-E1 with 35mm lens at f/1.4.

Tuesday, January 27, 2015 |

Tuesday, January 27, 2015 |  Post a Comment in

Post a Comment in  photo of the week | tagged

photo of the week | tagged  35mm 1.4,

35mm 1.4,  fuji x-e1,

fuji x-e1,  puerto rico,

puerto rico,  san juan

san juan

Old San Juan, Puerto Rico. Fuji X-E1 with 35mm lens at f/1.4.

Tuesday, January 20, 2015 |

Tuesday, January 20, 2015 |  Post a Comment in

Post a Comment in  photo of the week | tagged

photo of the week | tagged  35mm 1.4,

35mm 1.4,  fuji x-e1,

fuji x-e1,  puerto rico,

puerto rico,  san juan

san juan I've been doing some consulting work which has yielded some "fun money," so I've been able to pick up a couple of new lap steel instruments recently. The first was the 1930 National Tricone Squareneck I grabbed at the Philadelphia guitar show in November. Following with my growing interest in the lap steel, I've been wanting a Weissenborn-style guitar as well, and luckily one just fell into my lap (pun intended).

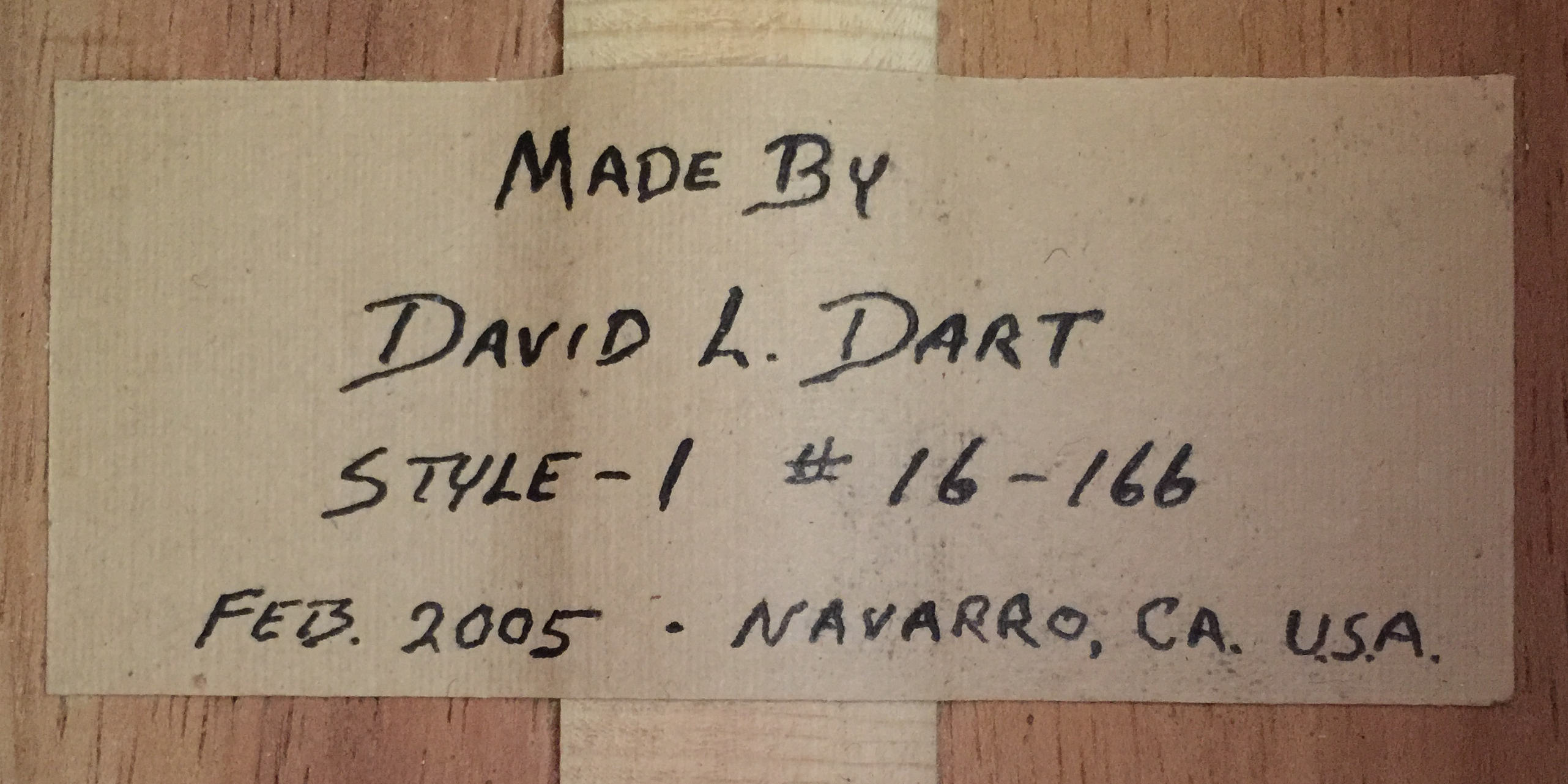

David Dart* is a California luthier who began building in 1966 and has made a few hundred instruments in that time, including guitars, mandolins, and Hawaiian lap steel guitars. His clients have included Ben Harper and David Lindley, and I just stumbled into a used Style 1 Hawaiian (i.e., "Weissenborn-style") all-koa guitar at an amazing price.

Update (3/13/15): Here's an interview with David Dart from the Fretboard Journal.

Read more about this history of Weissenborn-style guitars here, here, and here.

*I bought the guitar used from a shop in Los Angeles and have not met or spoken with Mr. Dart. This info comes from his website and other sources I found online. If you are looking for a similar guitar, I encourge you to commission one directly from him since (a) supporting independent luthiers makes for good karma, and (b) his instruments don't hit the market very often.

Update (2/8/15): As I've been doing more reading on the history of Hawaiian guitar I'm coming to understand that calling these "Weissenborn-style" instruments is inaccurate, although that term is commonly used. Although Hermann Weissenborn certainly made (relatively) many guitars in this style, the design of these instruments was not original to him. Read more here, and also check out the book by Noe & Most (1999), Chris J. Knutsen: From Harp Guitars to the New Hawaiian Family.

Basketball court at dusk in the La Perla neighborhood of Old San Juan, Puerto Rico. Fuji X-E1 with a 10-24mm lens at f/4.

Tuesday, January 6, 2015 |

Tuesday, January 6, 2015 |  Post a Comment in

Post a Comment in  photo of the week | tagged

photo of the week | tagged  10-24mm,

10-24mm,  fuji x-e1,

fuji x-e1,  la perla,

la perla,  puerto rico,

puerto rico,  san juan

san juan This video is from 2001 (a year after our van was built) and seems so dated now...

(my documents & links page has a section with Eurovan Camper files if you're looking for any EVC documentation.)

This is Part 3 of my series chronicling design, construction, and eventual delivery of a tenor guitar built by David Cavins. See Part 1 and Part 2 of this series.

We're now a couple of months into the process, and we have finalized most of the design decisions. David has also started construction on the top and back, and is currently getting ready to dive into the neck. Here are the specs:

While there are still a few design decisions to make, the guitar is starting to come together. David has been documenting the build process on his blog (see here). Here are some pictures I pulled from his site:

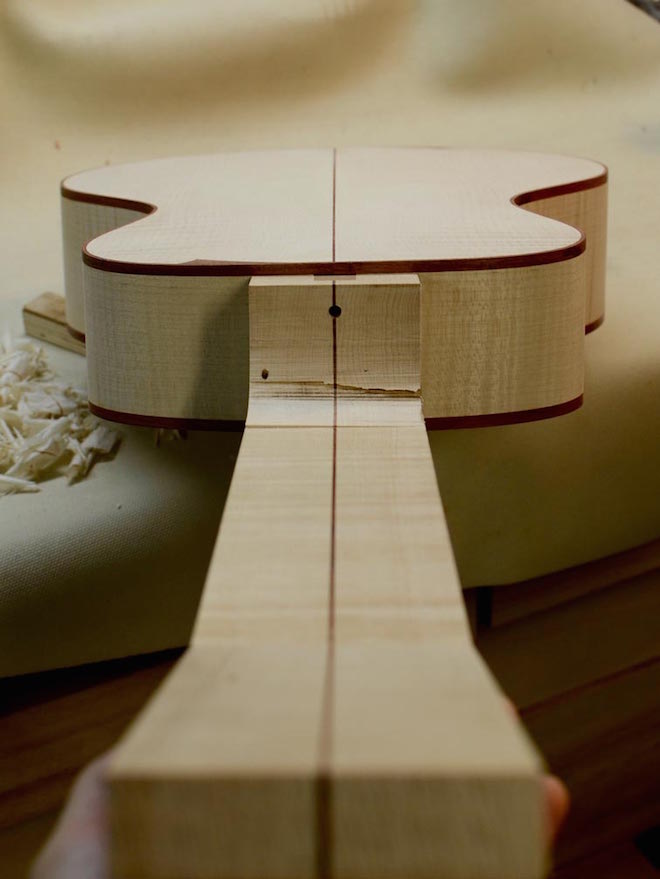

The sugar maple back, getting ready to be joined.

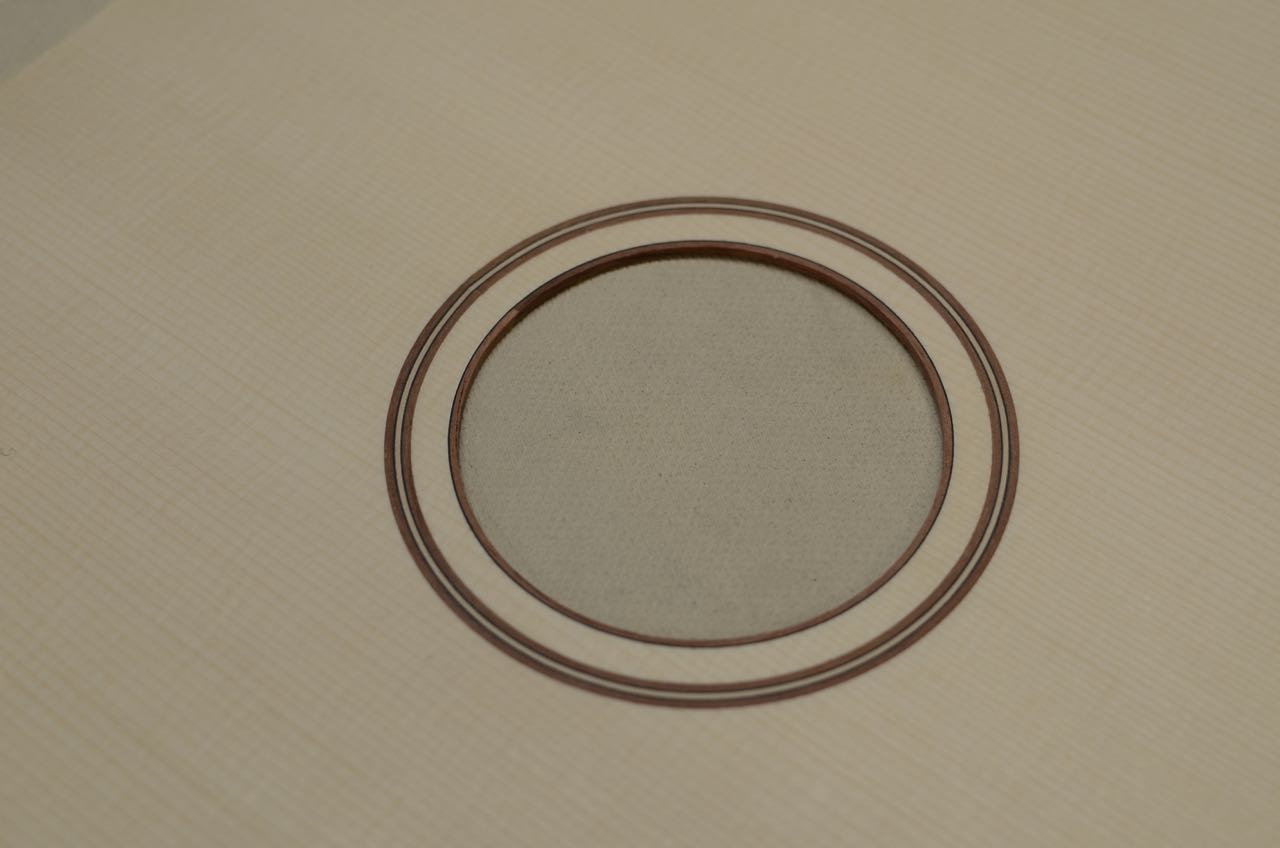

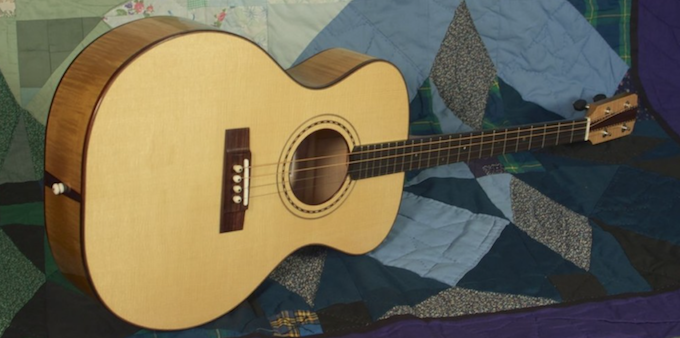

The Adirondack spruce top with the rosette installed.

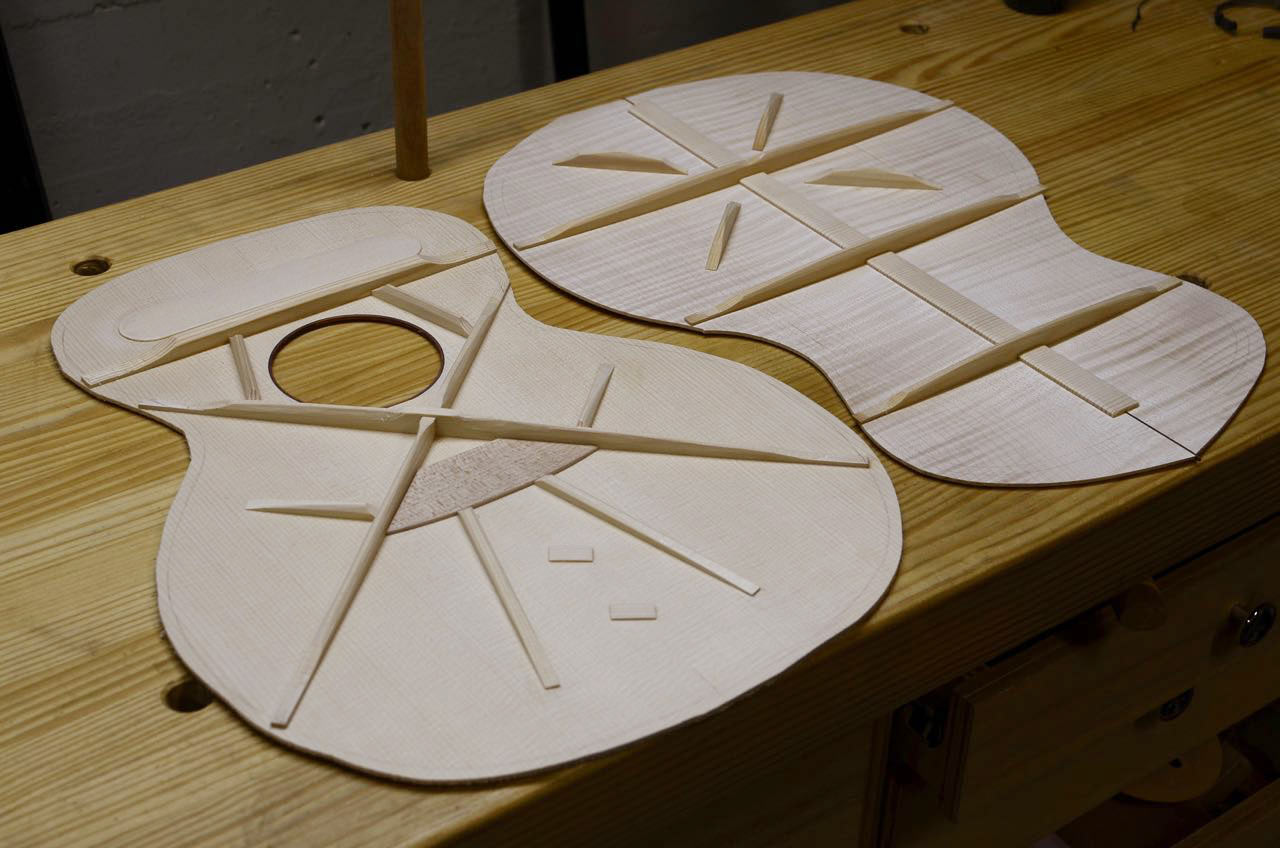

The top and back, with the rough bracing.

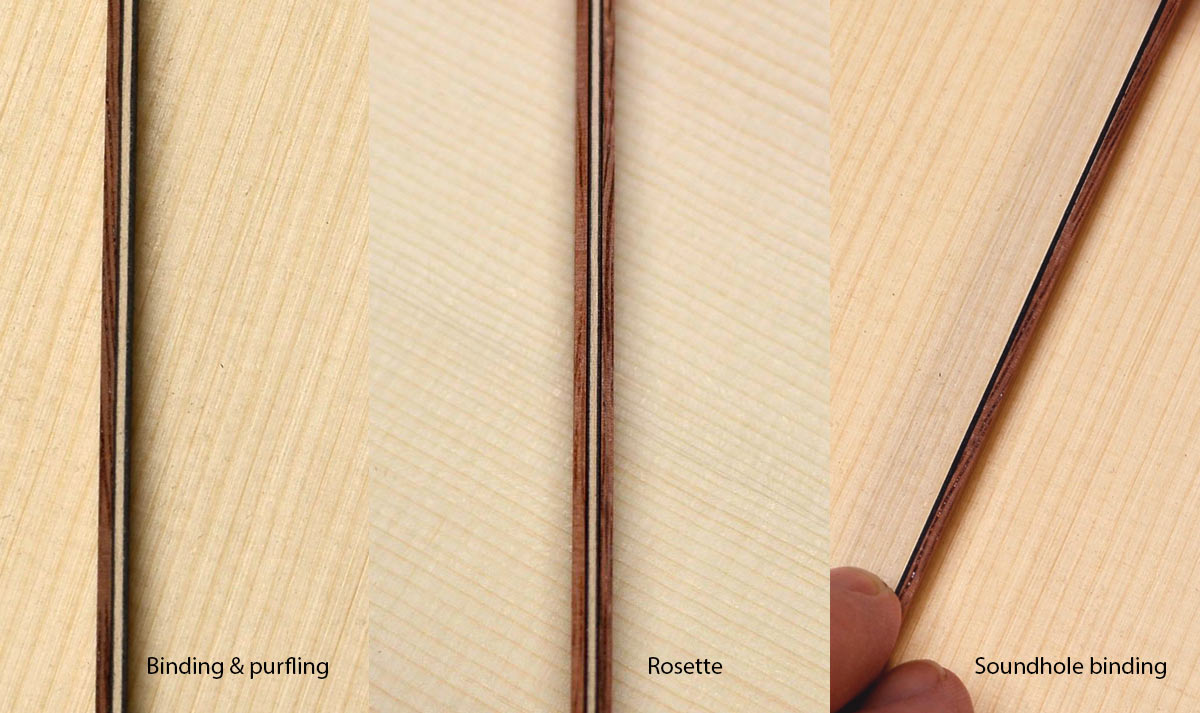

David put these samples together to show the accents. Understated, elegant, and classic.

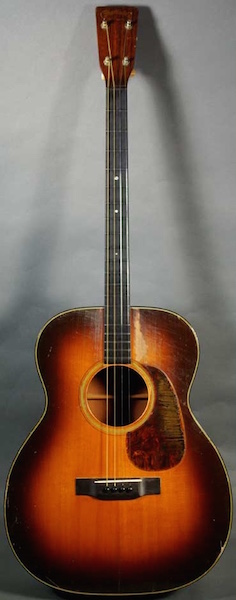

This is a previous tenor guitar he built in 2012, with a light sunburst finish on a sugar maple body. David photoshopped the version on the right to show me what it would look like with a backstrip. Mine will be similar (with the backstrip), with a slightly darker full-body sunburst.

A couple of years ago I posted on "what I'm GAS-ing for..." (i.e., what Guitars I wished I could Acquire, which is a bit of a Syndrome). Here's an updated list of what I'm currently lusting after:

Ben Harper and his Weissenborn.Surprisingly, that's about it. I've pretty much satiated my desire for guitars, other than what's above. I have a banjo, mandolin, ukulele, and a couple of resonators, so I'm pretty much flush. At least until I take up the fiddle :-)

Ben Harper and his Weissenborn.Surprisingly, that's about it. I've pretty much satiated my desire for guitars, other than what's above. I have a banjo, mandolin, ukulele, and a couple of resonators, so I'm pretty much flush. At least until I take up the fiddle :-)

It's interesting to see that the 2012 and 2014 lists are pretty different. It's not that I've aquired everything (or anything, for that matter) from the 2012 list. But tastes and interests change. As much as I'm first and foremost a guitar player, my interest in banjo and resonator guitars has taken center-stage recently. That being said, all of the stuff on the 2012 list is still appealing to me. I was seriously considering a Martin OM-18 Authentic as my 40th birthday present, but ended up going for a Collings D1ASB instead. Would still like that Authentic, though.

Now that I'm becoming proficient on a few different stringed instruments, most notably the banjo and lap-slide guitar in addition to guitar, I've been looking for a way to deal with with increase amount of gear that comes with these. In particular, my desk had become a mess of capos, finger- and flat-picks, and slides. In addition to desktop organization, being able to have everything in one place and ready to grab to take to a jam is important. I looked into little boxes and containers, but nothing seemed to work for this assortment of bits (i.e., some long, heavy, skinny things like slides and dobro capos; metal finger-picks that shouldn't get squished; my favorite picks that are easy to lose).

It dawned on me that a tool rool, like I've seen bicylists use (and seem popular with motorcyclists) might work. I ended up googling "waxed canvas tool rool" and ran across the Coffin Tool Roll by Red Clouds Collective. At $65 it's not cheap, but it's handmade by hipsters in Oregon and is a quality product that should last a lifetime. Along with multiple slots/pockets, it has a zippered pouch that seemed perfect for securing those little pieces (like picks) that are easy to lose. I found a 10% off coupon code which basically offset the shipping, and a few days later it arrived.

Rather than calling it a "guitarist's tool roll," which makes me think of the things like truss rod wrenches and small screwdrivers to tighten tuners etc., I think of it as a "guitarist's toy roll" since it's for all the little gadgets and gizmos that are commonly used in playing acoustic music.

Although we moved into our apartment more than two years ago, I finally finished setting up my office last month. And with winter just around the corner (i.e., low humidity), I've been looking into ways of humidifying the room so that I can keep some guitars out on stands without worrying about them getting too dry. The buidling is an old converted schoolhouse with radiators, and the humidity can get really low in the winter. I set up a small Holmes humidifier that we've had forever, but had been boxed up since a previous move about 10 years ago. It did the job, but it was way too loud for an office.

Although we moved into our apartment more than two years ago, I finally finished setting up my office last month. And with winter just around the corner (i.e., low humidity), I've been looking into ways of humidifying the room so that I can keep some guitars out on stands without worrying about them getting too dry. The buidling is an old converted schoolhouse with radiators, and the humidity can get really low in the winter. I set up a small Holmes humidifier that we've had forever, but had been boxed up since a previous move about 10 years ago. It did the job, but it was way too loud for an office.

Based on some online recommendations, I picked up a Venta Airwasher LW25, which has a 2 gallon tank and is made for rooms up to 400 square feet. What I like about this unit is that (a) it doesn't need any replaceable wicks, (b) the tank can be easily filled (i.e., pour water directly into the unit), and (c) it's supposedly pretty easy to clean. And the best part is that it's really quiet. On the lowest fan setting, it's basically silent. At medium, it's no louder than the street traffic I can hear from my office (I haven't needed to turn it to the highest fan setting yet). So far, so good; it works like a charm, keeping my office at 45-55% humidity without any problem.

Update: On the coldest days during the winter, when it gets down in the 20s, I find that I still need to run the small, loud Holmes humidifier along with the Venta to get up to the 45-50% range. The Venta alone can keep things in the mid-30 to low-40% range, which is probably fine but I'm being extra careful. So I run the supplemental humidifier at night and when I'm not in the office, and turn it off when I'm working in that room. Although the Venta should be fine for the square-footage of the room, I forgot to account for the high ceilings; the total volume of air is more than the typical 400 square foot room.* I probably should have gone with the largest Venta rather than the medium size.

*Why do they sell humidifiers based on square footage of the room? It should be cubic feet.

I have become increasingly enamored with my Beard Vintage R squareneck resonator recently. I've had it for years, but have just rediscovered it in the back of my closet. While I’m clearly still a beginner, I can play proficiently in an intermediate bluegrass jam, assuming things stay in the key of G or A.

Over the weekend I headed over to the semi-annual Philadelphia Guitar show. I hadn't been in a couple of years, and I’ve never purchased a guitar there, but it’s a fun way to spend a couple of hours. Since I’m pretty flush with flattop guitars, other than the vintage Martins and Gibsons I couldn’t afford, I spent more of my time browsing the vintage Dobros, Nationals, and other lap steels. There were a couple of interesting Gibson house-brand instruments with original Hawaiian set-ups (a blond Kalamazoo Oriole and a sunburst Recording King Carson Robison Model-K), but the guitar that captured my attention was a National Style 1 Squareneck Tricone.

This particular National was being offered by a dealer from Arkansas who had made his way up to Philadelphia for the show. He acquired the instrument from the family of the original owner in Kansas City. The serial number dates it to 1930, and it is in remarkable condition. There are no big dings or dents, and it is purported to be all original, including the tuners (i.e., have the correct engravings) and cones. The dealer even mentioned that the screws on the coverplate look untouched, so the coverplate may never have been removed.

![]()

![]()

This is Part 2 of my series chronicling design, construction, and eventual delivery of a tenor guitar built by David Cavins. See Part 1 here.

As David and I begin discussing this project, he asks me think about what I want it to sound like. But rather than only sticking to the standard lexicon that guitar geeks use (e.g., “warm,” “dry,” “woody”, “lush”, etc.), he encourages me to come up with some other descriptive works to translate the sound in my head into other modes. Here’s a snippet of the email I wrote, trying to capture these sounds:

"Spicy, but like wasabi, rather than jalapeños...there's heat, but it decays quickly so that the flavor of each string can shine.

Another flavor that might be a good descriptor is grapefruit: refreshing, some edge to it, with a shade of sweetness. Not as light or sweet as lemonade; more personality than orange juice.

Translating sound to color, I'm thinking orange. But not electric or neon orange, but instead the vibrant, organic orange of leaves changing color in the fall."

Amazingly, this description makes sense to him. He also has me write about other guitars that I’ve played and liked/disliked, so that we can get on the same page about how we hear and describe acoustic instruments. I tell him about my new Collings D1A, what I like about D-18s, what I dislike about a particular guitar that a friend of mine owns, and I try to describe my playing style and goals.

With this information in mind, we schedule a phone call. Although we spend part of that 90 minutes catching up, most is spent talking guitars. It's a joy to hear David's familiar voice after all of these years, and to be able to tap into his experiences with different design philosophies, construction techniques, and tonewoods is amazing. I learn how David approached the first guitars he designed, building them in pairs with everything the same (or as close as possible) except for one parameter that he’d change. As a scientist, I appreciate this process, and as a guitar geek (and builder of one instrument), I know enough to be dangerous. I learn about the “live back” that he builds...that he doesn’t just want the back to reflect the vibrations that the top produces, but that the back itself can generate sound.

David and I have similar values when it comes to the sociopolitical and environmental issues surrounding wood. He aims to source as much of his tonewood locally as possible, and avoids endangered, or questionably harvested, woods. I’m on board with this 100%. I think that generally the acoustic guitar market is so focused on particular tonewoods that it has ignored (a) the excellent sustainable materials available right in our own backyards (figuratively and literally) and (b) the luthier has a huge part in putting his/her stamp on the tonal signature of the instrument with the design and construction choices that are made and implemented.

We decide to go with Appalachian (“red”) spruce for the top, and sugar maple for the back and sides. David is fortunate to have a top supplier of these materials near him in Missouri, and these are domestic woods that both will have the tonal properties that we are aiming for as well as being responsible environmental choices.

A Cavins tenor guitar in sugar maple; from cavinsguitars.com.

A Cavins tenor guitar in sugar maple; from cavinsguitars.com.

To date, David has build about 30 guitars, although some are unnumbered, so mine will be serial #19. He has built a couple of tenors previously, with a recent one also being red spruce and sugar maple. Now that we have the basic framework in place (e.g., the tonal goals and main woods selected), the next step will be some of the cosmetic choices...Stay tuned for Part 3.

image from sprucetreemusic.comWhat’s next, when you have several 6-string guitars, a 12-string, a banjo, a mandolin, a ukulele, and a dobro? A tenor guitar, that’s what!

image from sprucetreemusic.comWhat’s next, when you have several 6-string guitars, a 12-string, a banjo, a mandolin, a ukulele, and a dobro? A tenor guitar, that’s what!

A tenor guitar is an instrument that was popular nearly 100 years ago (read more here). It’s essentially a 4-string, short-scale guitar, although it’s often tuned to CGDA (low to high), like a viola/mandola, or to GDAE (low to high) like an octave mandolin, but, of course, with four instead of eight strings. Admittedly, I’m brand new to the tenor world, but I’m intrigued and think there’s a lot of fun to be had playing one.

Why would one want a tenor guitar? For variety, of course! Chords will sound different, rhythm playing will be punchier, and you'll approach melodies differently than when playing a standard 6-string guitar. It’s good for my brain to figure out how to maneuver around different fretboards, and it will provide a new sound when playing with other people.

The usual suspects (i.e., Martin and Gibson on the high end, and lots of budget brands) built tenors back in the day, and a few contemporary builders (e.g., Collings) are doing them now. But since a tenor is totally new to me, and I don’t have any preconceptions of what one is supposed to be like, I figured it was time to venture away from factory instruments and work with a luthier on a custom build.

I met David Cavins just over 20 years ago, when we moved into the same dorm at Grinnell College. For the next two years, until I graduated, we ran in the same circles, playing music together, and cooking hot-as-can-be midwest-inspired Mexican food (potato and corn enchildas...yum!). David had an enthusiasm for everything he did, with an approach that always struck a balance between the analytical/scientific and artistic/aesthetic. He was (and is) one of the most thoughtful, open, and genuine people I've ever met, and he introduced me to Americana music, which has stayed with me to this day. However, once I went off to grad school and got immersed in my studies and subsequent career we lost touch, although I thought of him often.

In December of 2011 we reconnected, after David found my blog about the guitar building class I took at Vermont Instruments School of Lutherie. I was excited to be back in touch with him, and was especially thrilled to learn that he also had developed an interest in guitar building. However, while I'm a chroinc dabbler in things, David goes all in, and he was in the midst of setting up shop and developing his line of Cavins Guitars.

For the next few years we’d shoot email or tweets back and forth whenever we saw interesting articles about guitar building. But about a month ago, as I was thinking about tenor guitars, I asked David if he’d be willing to build one for me, and he agreed. What will follow over the next couple of months is a series of posts that will chronicle the build, from my end. This is going to be a fun project, and I can’t imagine doing it with anyone else but David.

For the next few years we’d shoot email or tweets back and forth whenever we saw interesting articles about guitar building. But about a month ago, as I was thinking about tenor guitars, I asked David if he’d be willing to build one for me, and he agreed. What will follow over the next couple of months is a series of posts that will chronicle the build, from my end. This is going to be a fun project, and I can’t imagine doing it with anyone else but David.

Monday, October 20, 2014 |

Monday, October 20, 2014 |  Post a Comment | tagged

Post a Comment | tagged  david cavins,

david cavins,  grinnell,

grinnell,  guitar,

guitar,  lutherie,

lutherie,  tenor guitar

tenor guitar